Welcome back to the Diamonds Hatton Garden blog where we bring you the latest insights from our Hatton Garden jewellers. Following on from our buying guides to various fancy cut diamond shapes, we look to continue with our educational themed blogs with today’s article looking at different diamond cuts. In our three part series we look at the three main types of diamond cuts: the brilliant cut, the modified brilliant cut and the step cut. Today we explore the history of the brilliant cut and what to look for when buying a brilliant cut diamond.

What is a diamond cut?

Before a diamond cutter chooses the specific cut of a diamond, they will analyse the rough diamond and note its unique inclusions and carat weight which impact the specific cut of the diamond. In most cases, a diamond will be octahedra, making it ideal for a round brilliant cut. Why is this? A rough diamond will be cut and polished into two faceted gems without it losing too much carat weight thus making the cutting more effective and wasting less of the rough. Therefore, a diamond cut determines the diamond’s fire, brilliance and scintillation levels; it’s the technical aspects used to maximise the diamond’s brilliance.

The Brilliant Cut – What we think of when we think of diamonds.

When we think of a diamond, most of us will imagine the standard diamond that we see across billboards, advertising and graphics. This shape of cut has become the international standard that almost all rough diamonds are cut to. This shape is called the Brilliant cut and refers to the optimal light return that this cut produces. When light falls onto a transparent gemstone it enters the stone and undergoes refraction. In order for the observer of a diamond to experience the stone’s ‘brilliance‘, light needs to be reflected within the gem so that it leaves the stone in the direction from which it came, allowing it to reach the observer’s eye. The Brilliant is the result of optimising this effect by fashioning the diamond in a specific way.

Diamond shapes of years past

In the ancient world, diamonds were prized for their supreme hardness. They represented invincibility and were worn by elites who saw their status reflected by this ultimate stone. Their beauty of the diamond was far less important than it is today. In fact, in the past diamonds were not nearly as attractive as those that we have in the modern World. Roughly around the end of the Middle Ages diamonds began to be cut, yet unlike today, they weren’t cut to maximise light refraction. The early table cut was used to show brightness but no way near on the scale that modern cuts provide. Indeed, other cuts were attempted that would capture the ideal shape with a crystal point which shows very reduced brightness and was cherished because the shape, when polished also produced surface reflection.

Around the 17th century diamond cutters in Europe, with the onset of technology and a change in style began to develop cuts and diamonds that sparkled like never before. A popular cut of the time, the Rose Cut, had numerous facets that reflected candlelight in all directions.

The Early Brilliant Cut

Many can lay claim to the modern brilliant cut, however it is widely accepted that Cardinal Mazarin commissioned the twelve largest French crown jewels to be recut into a ‘new design’. Unlike today where we have ideal proportions, round, oval and other shaped Brilliants were irregular and, over time began to become more uniform and standardised – something which would see successive modifications over time.

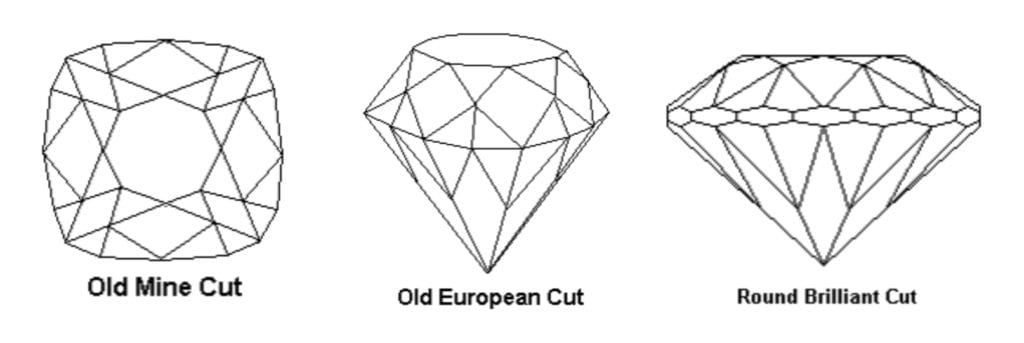

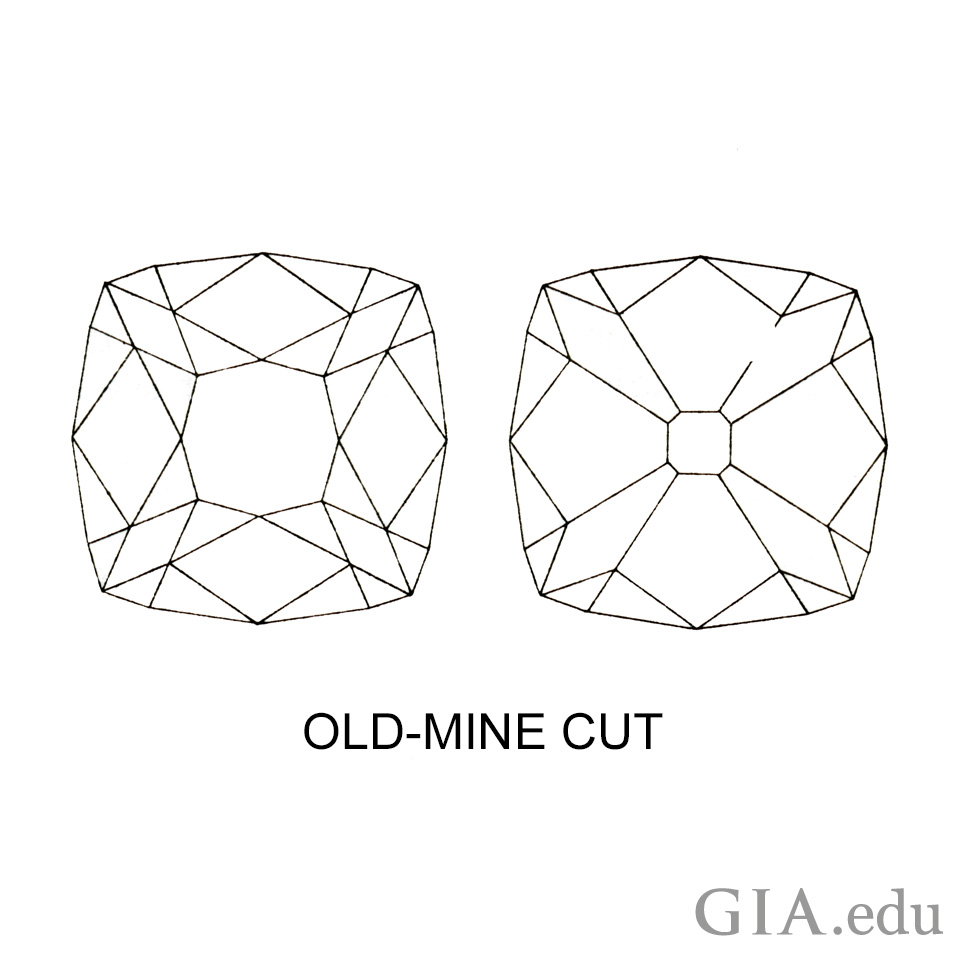

Old Mine Cuts

Early diamond cutters of this period began to introduce a symmetrical outline, a requirement for even facet distribution and were still extremely limited in their brilliance. Bruting still occurred by hand and was a time-consuming and difficult task. One also has to consider that shaping a stone to become symmetrical in its outline costs a lot of material. Weight has always been the decisive factor when pricing diamonds so cutters have alway been keen to retain as much weight as possible. This explains the predominantly squarish outlines of early brilliants. Most rough had square shapes as had the diamond cuts of the past which acted as a starting point: the great recutting of old cuts had begun.

The rise of the Brilliant coincided with depletion of the Indian diamond mines so at first, it was mainly existing Table and Point Cut stones which were recut into the new fashionable design. Many of the old Table Cuts had missing or blunted corners, a problem which the cutters solved by creating a square outline with rounded corners: a cushion shaped stone. When, around 1730, a steady production of Brazilian diamonds was realised most of this new rough was cut into cushion shaped Brilliants. The term used to indicate these brilliants of the second half of the 18th and most of the 19th century is the ‘Old Mine Cut’. The term was introduced in the late 19th century and is still encountered today.

Old European Cuts

The introduction of mechanical cutting devices revolutionised the diamond cutting industry and allowed for more precision, stanardisation and symmetry. European diamond cutters quickly adopted the use of machines and started producing Round Brilliants in vast quantities thus allowing the diffusion of the new cut to enter markets across the world. The products of these later 19th and early 20th-century cutting houses are called ‘Old European Cuts’, a term which indicates stones with round outlines, reasonable symmetry, octagonal table facets, deep pavilions, high crowns and short pavilion bezels.

The Standard Round Brilliant Cut

It wasn’t until the latter 19th century that the brilliant became to resemble the shape that we all know in the 21st century. Both American and Russian diamond cutters poured their craft into perfecting the shape to maximise brilliance and minimise waste. Early standardised brilliant cuts, much like today, were expected to show a well-balanced mix of brilliance and fire. As the proportions became standard over the course of the 20th century, the cut grew in popularity before becoming the symbol itself of the diamond.

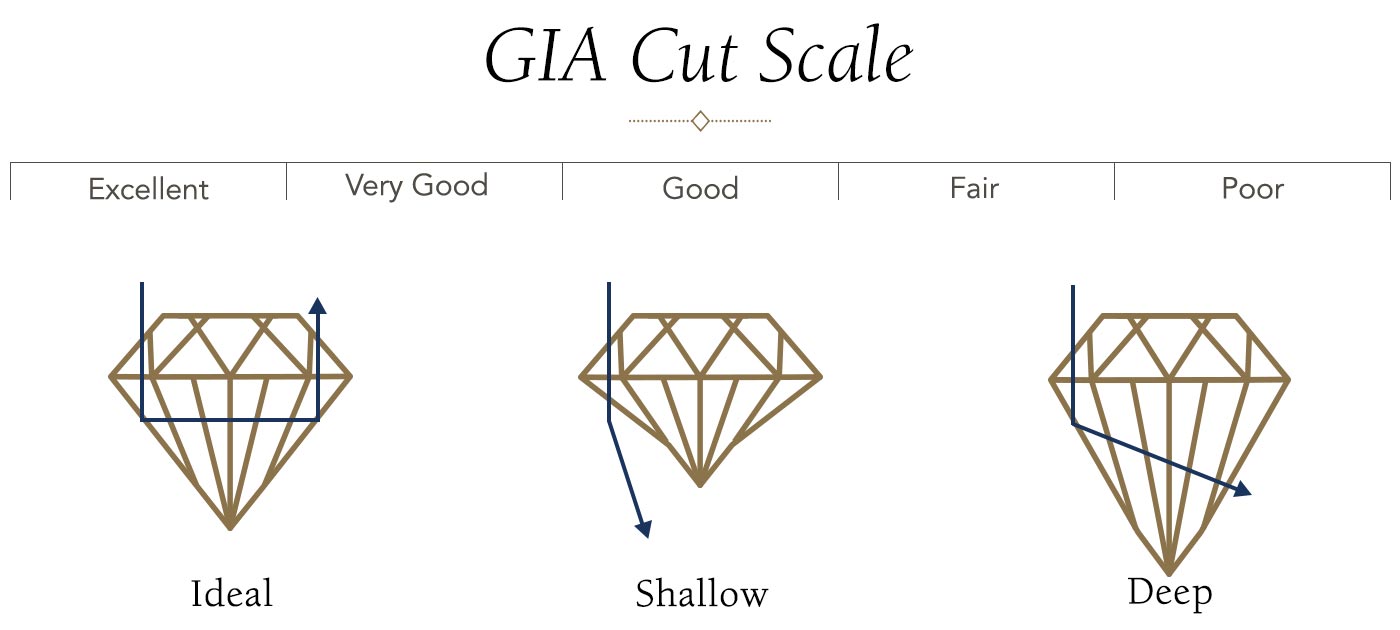

Recommended Proportions

| Excellent | Very Good | Good | Fair/Poor | |

| Table % | 54% – 57% | 53% – 60% | 51% – 62% | Outside Ranges |

| Depth % | 61.0% – 62.5% | 60.0% – 63.0% | 59% – 64% | Outside Ranges |

| Polish/Symmetry | Excellent – Very Good | Good | Outside Ranges | |

| Crown Angle | 34.0 – 35.0° | 33.0 – 36.0° | 32.0 – 37.0° | Outside Ranges |

| Pavilion Angle | 40.6 – 41.0° | 40.2 – 41.4° | 39.8 – 41.8° | Outside Ranges |

| Girdle Thickness | Thin – Slightly Thick | V. Thin – Thick | Outside Ranges | |

| Culet Size | None | Very Small | Small | Outside Ranges |

What colour to choose?

Due to their facet pattern and cutting style, round diamonds reflect more light than any other diamond cut. This means that the colour tint of a round diamond can be hidden by the sparkle meaning that a high colour grade is not required for the diamond to have a white appearance. We recommend colours around the G which allow for other important factors of the 4 Cs to be considered allowing for an all round diamond that will look beautiful,

What clarity to choose?

We believe that eyeclean stones tend to offer the very best value for money and, much like choosing a G coloured stone, allow for the budget to choose a well-rounded stone. On average, most SI1 and VS2 diamonds will be eye clean and we believe that these grades offer the best value.

At Diamonds Hatton Garden our team of family-run jewellers have assisted generations of clients to find their perfect round brilliant diamond engagement ring. Contact our team via harel@diamondshg.co.uk or call +44 7951 060238 for more information and to arrange your appointment. Alternatively, explore our selection of fancy coloured diamonds for sale and if you are looking to buy fancy Pink diamond jewellery contact our team as well as viewing our latest Diamond engagement rings in Hatton Garden. Or contact our team to sell diamonds in London.